Retrofit and Modernize: A way forward for revamping legacy cold storages in India

Agriculture, one of the most important sectors of the Indian economy, has seen phenomenal growth in the production of perishable commodities, including horticulture produce. Among the horticulture crops, Uttar Pradesh was India’s largest potato producing state, followed by West Bengal, where 13.16 million metric tonnes (MMT) of potatoes were produced in 2019-20. However, investment for cold chain development in India, particularly West Bengal, undermines the importance of a climate-friendly uninterrupted cold chain as an essential requirement for the potato value chain. This blog briefly presents the highlights of our study on potato value-chain in West Bengal, focusing on assessing the cold storage industry in West Bengal, especially the different aspects of the potato value chain, highlighting the effect of inadequate cold storage infrastructure on the produce quality, food and associated monetary loss. The study also suggests the way forward by modernising and retrofitting the existing cold-chain infrastructure to avoid food loss and improve the energy performance of the cold storages.

Potato Value Chain in West Bengal

Key facts about Agriculture in West Bengal

Key facts about Agriculture in West Bengal

West Bengal is an agricultural economy with 44% of its total workforce dependent upon agriculture. It ranks as the second-largest horticultural crop-producing state in India, after Uttar Pradesh. Potato (primary horticultural produce of West Bengal) plays a vital part in the agricultural economy of West Bengal, which is majorly grown in Hooghly, Burdwan, Bankura and Medinipur districts of West Bengal. In 2019-20, of the 13.16 million metric tons of potatoes produced in the state, 4.37 million metric tons were consumed by the domestic consumers, 6.79 million metric tons were exported to the other states, and the remaining 2 million metric tonnes was lost during the intermediation process.

The potato supply chain involves several intermediaries ranging from village traders, cold storage owners, commission agents to wholesalers and retailers. The harvested crop is generally sold to village traders, as ‘mandis’ and wholesalers are not accessible to most potato farmers in West Bengal. As a result, a farmer earns an average of INR 5 per kilo of the table variety of potato in West Bengal. In contrast, the average farmgate potato price in Gujarat comes about approximately INR 9.65 per kilo.

Potatoes are usually stocked in cold storages to improve their shelf life. There were 514 cold storages in West Bengal in August 2020, out of which 90% (463 cold storages) were used to store potatoes. The average capacity of cold storage dedicated to potatoes in West Bengal is around 11,000 MT. The cold storages are used from the end of February when the produce starts coming in. The stored potato stock begins depleting from May until the end of the storage season, usually November. Peak season utilisation sees 100% of the storage capacity being utilised, which gradually declines, starting from May to the end of the season, i.e. November, as the stocks are unloaded. Currently, the storage rate in West Bengal is INR 157/quintal/season.

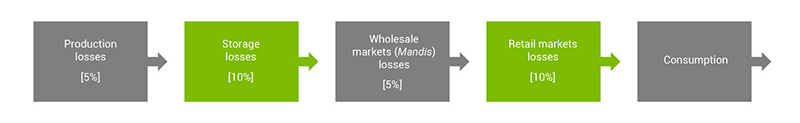

As part of this study, Alliance for an Energy Efficient Economy (AEEE), with support from the Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL), conducted detailed energy audits of three different types of cold storage facilities located in the Hooghly district of West Bengal to understand the potato handling, storage practices, and energy utilisation. The study revealed that more than 25% post-harvest losses occur (shown in figure below) in the supply chain of potatoes in West Bengal during production in cold storages, wholesale markets, and retail outlets due to improper handling, and storage procedures.

Post-harvest Losses in the supply chain of potatoes in West Bengal

Post-harvest Losses in the supply chain of potatoes in West Bengal

It was also observed that with traditional bunker coil systems and single chamber designs, the desired air circulation, temperature, and humidity conditions are challenging to maintain. Infiltration losses are common due to leaky building envelopes. The average unit rate of electricity purchased from the grid varies from INR 7 to 8 per kWh among the audited facilities. More than 90% of the energy expenditure was attributed to the electricity grid, with the remaining 10% supplemented with diesel generators.

The team estimated that around 0.38 MMT of potato losses and approximately 25% of energy requirement could be reduced by modernisation of cold storages in West Bengal, leading to a monetary benefit of INR ~662 crores (EUR 78 million) per year. The modernisation should also focus on improving the thermal performance of the building envelope and optimising the overall refrigeration system performance to improve the energy performance of cold storages. The overall investment required for modernising the cold storages is around INR 1750 crores (EUR 205 million). Factoring the Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH) subsidy support of 40% on the overall investment, the effective payback period comes to be 1.6 years.

In conclusion, the report analysed the state-level energy-saving potential, investment potential, and the monetary benefits from potato loss reduction through the modernisation of cold storages in West Bengal.

Way forward for West Bengal to capitalise their potato produce to its full potential

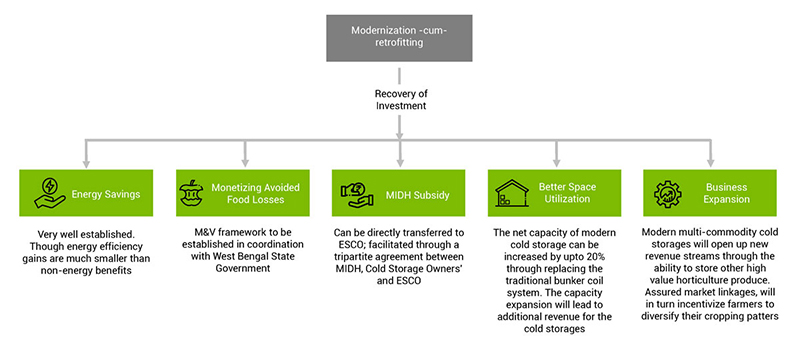

The state has vast growth potential in the horticulture sector, requiring a shift from cold storages to integrated cold chains to realise its full potential. Modernisation cum retrofitting of the existing traditional cold storages into multi-purpose cold storages will be the right step. This step will also incentivise diversification of the cropping pattern, bringing new avenues of growth for the farmers. Moreover, the multiple benefits of modernisation, generally underestimated worldwide, will significantly outweigh the energy savings considered in isolation. It will help the farmers to realise a greater economic value for their produce and boost their income.

West Bengal, a prominent horticulture producing state in the country, should set the pace for other states to follow. West Bengal Department of Food Processing Industries and Horticulture should lead the development of a cold chain action plan, outlining the approach and benefits of a modern, environment-friendly cold storage value chain in the state. The policy document should introduce state-level subsidy support to supplement the central MIDH as Viability Gap Finance to make the retrofitting-cum-modernisation scheme financially viable. Moreover, the below figure also suggests some of the possible options for recovery of investment for modernising-cum-retrofitting that can support modernisation of the existing cold storages; organisations such as EESL can facilitate modernising-cum-retrofitting of cold storages in West Bengal.

Possible Options for Recovery of Investment for Modernising-cum-Retrofitting

Possible Options for Recovery of Investment for Modernising-cum-Retrofitting

To access the full report, please see Analysis of cold storage infrastructure in West Bengal- Retrofitting opportunities in the ESCO model

This blog is written by Tarun Garg and Khushboo Gupta. While Khushboo is presently working as a Senior Research Associate in the Buildings and Communities vertical, Tarun leads the vertical at AEEE.