Cooling the Future: Making District Cooling a Core Infrastructure in India’s Urban Strategy

With record-breaking summers a yearly phenomenon for Indian cities, surging cooling demand is straining power grids, threatening energy security, and challenging the sustainability of urban development. With cooling needs projected to grow eightfold by 2037–38 (India Cooling Action Plan, 2019), infrastructure planning must evolve. Yet, the way we currently approach this challenge, treating cooling as a building-level service rather than essential urban infrastructure, is no longer viable.

To address this, Shared Cooling Infrastructure (SCI), also known as District Cooling Systems (DCS), emerges as a future-ready solution that can be central to India’s infrastructure and climate strategies. DCS is not just a technology – it’s a scalable urban utility that aligns with national priorities for clean energy, water security, and economic resilience.

Rethinking Cooling as Urban Infrastructure

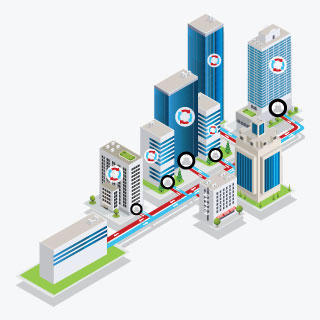

District Cooling Systems work by producing chilled water at a central plant and distributing it to multiple buildings through an underground pipeline network. This model replaces the need for thousands of individual air-conditioning units in commercial complexes, hospitals, campuses, and residential clusters. Due to the aggregation of cooling demand, DCS can optimise the system size and operations, leading to higher capacity utilisation.

The benefits are transformative:

- Reduction in Installed Cooling Capacity of up to 30%[1].

- Peak electricity demand is reduced by consolidating cooling loads, also the shifting of peak electricity requirement via the use of thermal storage.

- Energy efficiency improves due to economies of scale and the use of high-efficiency chillers.

- Cost avoidance as equipment like Chillers, Cooling Towers, etc, is not required at the building level; Lifecycle savings up to 25-30%[2].

- Water use can be optimised through treated wastewater and seawater, supporting circularity in resource use.

Moreover, DCS can be integrated with solar and wind energy, waste heat from industrial zones, waste energy from municipal solid waste, and treated water from sewage treatment plants (STPs). This integration allows DCS to reduce dependence on conventional energy sources while promoting energy and resource circularity by harnessing resources that would otherwise go unused or sub-optimally utilised. GIFT City in Gujarat is a notable example, where DCS, powered in part by solar energy and treated STP water, has helped reduce grid reliance while meeting a significant portion of the system’s cooling and water needs.

Quantifying the Opportunity

As per an EESL-UNEP report[3], under an optimistic scenario, the DCS installed capacity in 21 tier 1 and tier 2 Indian cities can reach ~13 million TR (Ton of Refrigeration), 300+ DC Plants, by 2037-38, resulting in estimated savings of:

- 7,850 GWh of annual energy consumption

- 78,850 million litres of potable water

- USD 10.5 billion in infrastructure investment

This isn’t just about technology, it’s about better planning for resilient, climate-adaptive cities. And to make this happen, District Cooling must be formally recognised as a core infrastructure.

Unlocking DCS Through the Harmonised Master List

The Harmonised Master List (HML) of Infrastructure Sub-sectors, curated by the Department of Economic Affairs (Ministry of Finance), is India’s tool for guiding infrastructure investments and policy. It categorises key infrastructure areas, like transport, water, power, and digital connectivity, so they are eligible for concessional financing, tax incentives, regulatory support, and long-tenor funding from pension and insurance funds.

Importantly, the HML also facilitates better coordination among agencies responsible for infrastructure development. As noted in the 2012 Press Information Bureau release[4], “harmonization of the existing definitions of infrastructure sectors will facilitate a coordinated approach among agencies providing support to infrastructure, and thus spur infrastructure development in a more optimal manner.” This is particularly relevant for complex systems like District Cooling, which require alignment between urban development authorities, electricity utilities, and financial institutions for successful implementation.

HML also serves as a gateway to infrastructure lending by:

- Enabling access to larger External Commercial Borrowings (ECBs)

- Allowing borrowing under enhanced exposure norms

- Facilitating funding from institutions like IIFCL (India Infrastructure Finance Company Ltd)

Over time, HML has been updated to reflect new infrastructure needs, such as the inclusion of data centres and energy storage systems in 2022. The inclusion of District Cooling Plants and distribution pipelines can be an important next step, especially as India scales up its energy-efficient and climate-resilient infrastructure portfolio.

Why This Recognition Is Critical

India is poised to add over 130–150 million new room air conditioners over the next decade, which could push peak power demand up by 180 GW by 2035[5]. Without strategic interventions, this demand surge could overload electricity systems and undermine India’s net-zero ambitions.

Recognising DCS as infrastructure would:

- Catalyse private and public investments in centralised cooling

- Improve the bankability of DCS projects by unlocking financial and policy support

- Help meet cooling needs without increasing the carbon and energy intensity of cities

- Complement national priorities, such as the India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP), Smart Cities Mission, and the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP)

Bridging the Gap: From NIP to HML

The National Infrastructure Pipeline, launched in 2020 by the Department of Economic Affairs, laid the foundation for investing INR 111 lakh crore[6] in infrastructure across India. However, the current phase concluded in March 2025. As India revises or renews its infrastructure roadmap, the next wave of urban investment must prioritise forward-looking solutions like District Cooling.

While NIP offers a macroeconomic framework, it is the HML that provides legal and financial teeth to infrastructure recognition. This is why the inclusion of DCS in the HML is not just symbolic – it is instrumental to accelerating deployment and mainstreaming DCS as a service model.

From Heatwaves to Resilience: A Policy Vision

With 57% of Indian districts – home to nearly three-fourths of the population – now facing high to very high heat risk[7], cooling has become a public necessity, not a luxury. But if India simply meets this demand through conventional cooling technologies, we risk locking into inefficient, carbon-intensive growth, considering conventional cooling systems require planning for a bigger electricity supply infrastructure, also energy inefficient compared to DCS.[8]

District Cooling offers a resilient, scalable, and low-carbon pathway to cool Indian cities. But for it to flourish, it must be recognised as critical infrastructure, not merely an energy intervention or a niche urban utility.

A Vision for the Future

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi aptly stated, “Infrastructure is much more than cement and concrete. Infrastructure guarantees a better future. Infrastructure connects people.”

District Cooling embodies this ethos by linking sustainability with economic development and urban comfort with climate resilience.

Imagine a future where India’s cities are not just growing, but cooling smartly, where urban development doesn’t compromise on livability, and infrastructure isn’t just reactive but resilient by design.

To achieve that future, integrating District Cooling into India’s Harmonised Master List of Infrastructure Sub-sectors is not just advisable, it is necessary. It will empower cities to meet surging cooling demands sustainably and ensure that India remains on course toward its climate, energy, and urbanisation goals.

[1] Jakobsson, M., & Lundberg, P. (2024). Asia Pacific district cooling outlook. Hot Cool, (8). https://dbdh.org/asia-pacific-district-cooling-outlook/

[2] Adani Energy Solutions Ltd. (n.d.). Cooling solutions: Transitioning to sustainable and low carbon cooling solutions. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://www.adanienergysolutions.com/cooling-solutions/

[3] Energy Efficiency Services Limited & United Nations Environment Programme. (2021). National District Cooling Potential Study for India (Final report).

https://eeslindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Final‑Report_National‑District‑Cooling‑Potential‑Study‑for‑India.pdf

[4] Press Information Bureau. (2012, March 1). Harmonized list of infrastructure sub-sectors [Press release]. Government of India. https://www.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=80634

[5] India Energy & Climate Center. (2025). India can avert power shortages with stronger AC efficiency standards: Study [Working paper]. University of California, Berkeley. https://iecc.gspp.berkeley.edu/resources/reports/ac-efficency-standards-report2025/

[6]Press Information Bureau. (2023, January 31). Ministry of Finance [Press release]. Government of India. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894919#:~:text=The%20government%20launched%20the%20National,quality%20infrastructure%20across%20the%20country.

[7] Prabhu, Shravan, Keerthana Anthikat Sukesh, Srishti Mandal, Divyanshu Sharma, and Vishwas Chitale. 2025. How Extreme Heat is Impacting India: Assessing District-level Heat Risk. New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

[8] Danfoss. (n.d.). District cooling. Danfoss. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://www.danfoss.com/en-in/markets/district-energy/dhs/district-cooling/#tab-overview

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of AEEE

This blog is written by – Pramod Kumar Singh, Vibhu Saxena