Economic and behavioural policy implications of biodiversity loss and natural capital depletion

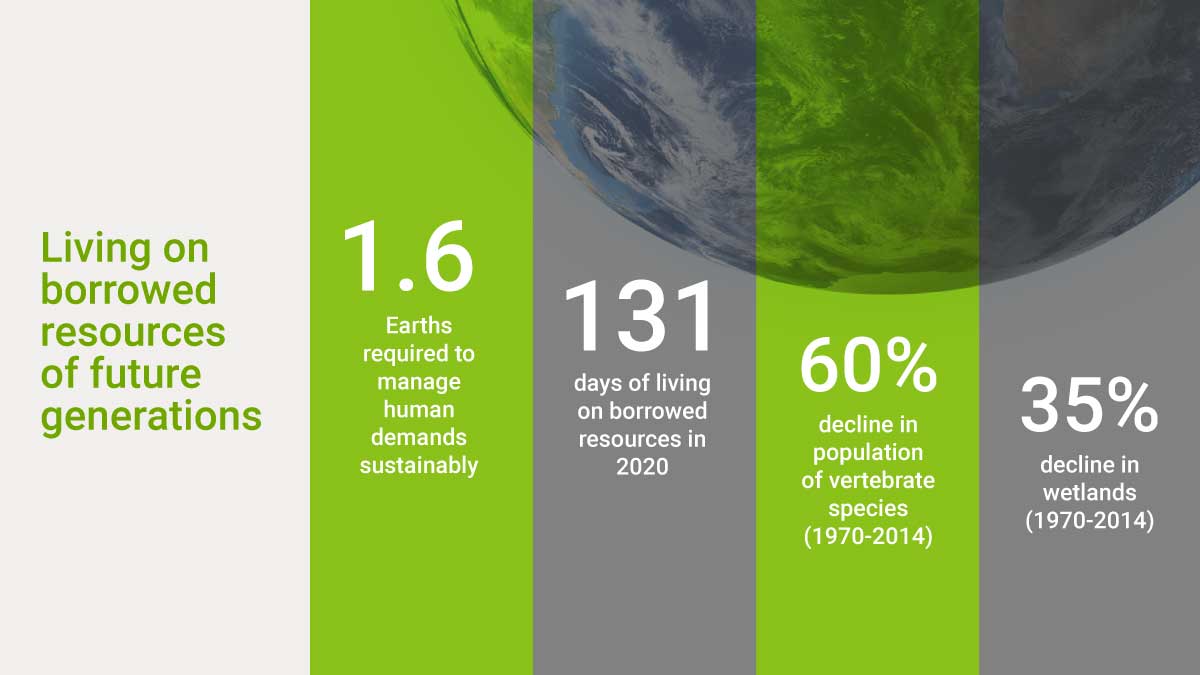

An overall decline of 60% in the population sizes of vertebrate species and 35% of the world’s wetlands between 1970 and 2014 is a stark reflection and ultimate indicator of the pressure humans exert on the planet.

Nature conservation is not just about protecting our diverse species of tigers, giraffes, polar bears and conserving the ecosystem. It’s bigger than that. The rapidly deteriorating natural capital has direct implications on our lives, health and livelihoods. Humans’ closely and intricately knitted relationship with the planet and its resources simply implies that biodiversity is the web of life that sustains us all.

Speaking about the risks that natural capital degradation imposes on human health, economy, and society at OECD’s Green Growth and Sustainable Development (GGSD) Forum, Sir Parthadas Gupta underscored the close interlinkages between the economy and natural environment.

Key takeaways:

Thresholds and irreversibility

Risks of biodiversity loss are exacerbated by the non-linearity of ecosystems, which also became apparent with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many ecosystems are already reaching their tipping points and it is far costlier and more difficult to restore an ecosystem once it has reached an unproductive state. Immediate action will not only be less costly, it would be also help achieving far more societal goals including alleviating poverty and mitigating climate change.

Externalities

Biodiversity loss is not reflected in market prices as nature is a public good, open to all. Also, nature is mobile, silent, and invisible. Such externalities make it hard to account for losses. However, biodiversity loss and natural capital depletion are not just a case of market failure but also an institutional failure. Governments exacerbate the problem by offering nature subsidies.

Ecosystem-Economy Nexus

It is important for governments to acknowledge that economies are embedded within nature. In that context, it becomes important to change how we think, act and measure economic success, within the nature’s constraints.

Speaking from an economic perspective, three broad transitions are needed:

- Address the imbalance between the demand and nature’s supply which means conserving our natural assets as well as reducing our global ecological footprint. Along with technological innovation, consumption and production patterns also need be altered. Managing growing population would also be important. Improving women’s access to finance and education, community-based family planning can accelerate the demographic transition.

- Measures of economic success need to be changed to guide us on a sustainable path. The impact of the current unsustainable consumption patterns must be accounted for and addressed. GDP is important for short-run macroeconomic planning; however, it fails to account for depreciation of natural assets.

- We must transform our institutions and systems to enable these transitions, investment decisions should take the nature into account, and citizens must be empowered to demand changes. There is growing evidence that testifies that human preferences are significantly influenced by the choices of others, which can be leveraged to amplify the desired action.

Inevitably, human behaviour and actions are at the centre of the pull and push that exists between our resource demand and the nature’s supply. Growing population and rising consumption imply a more tremendous strain over the Earth’s finite resources. To consume no more than the planet can provide, altering consumption patterns is vital. Opting for more plant-based diets, choosing cleaner fuels or using public transportation are all pro-environment actions that are embedded in human behaviour. Insights from social sciences, psychology and behavioural economics suggest that behavioural dimensions are equally, if not more, influential in shaping consumer responsiveness to regulatory and monetary interventions. To this effect, perhaps policymakers should be focusing on whether, and how behaviour change can be an important lever to reduce our ecological footprint.

Written by Simrat Kaur, Research Associate at AEEE