Strengthening Sustainable Cold-Chains in Rural India

The Case for Cold-chain in Agriculture and Healthcare Sectors of India

While it is said that India has almost reached production (agricultural produce) self-sufficiency, it is still ranked 101 out of 116 countries in the 2021 Global Hunger Index[1] and 71 out of 113 countries in the Global Food Security (GFS) Index 2021[2]. The lack of integrated cold-chain infrastructure, specifically the absence of adequate cooling and refrigeration technologies and post-harvest infrastructure in rural communities at a) farm-gate (point of harvest), b) collection point (aggregation), c) during transit, and d) at wholesale and distribution hubs, contributes to significant post-harvest losses in India, adversely impacting farmers’ income[3].

Several studies have indicated substantial post-harvest losses such as 15% in fruits and vegetables annually, as reported by ICAR-Central Institute of Post-Harvest Engineering and Technology (CIPHET) in their 2018-19 annual report. These produce related losses from farm to market create a huge burden on farmers’ hard-earned income. Farmers are India’s backbone as they play a vital role in India’s economy (54.6% of India’s total workforce is engaged in agricultural and allied sector activities as per Census 2011 data) by contributing around 17.8% of the country’s Gross Value Added (GVA) for the year 2019-20 [4].

Moreover, it has been reported that the total post-harvest loss accounts for a loss of 1 lakh crore INR annually[5]. This enormous monetary loss impacts a significant section of farmers, as most of the farmers engaged in horticulture crop production are small and marginal land-holder farmers, who account for 86%[6] of all farmers in India and own about half the arable land. Therefore, in the absence of affordable post-harvest management facilities, these small and marginal land-holder farmers are not able to store their produce and have to either sell it at a lower cost or face produce spoilage. Consequently, the small and marginal land-holder farmers struggle with low incomes and huge produce losses. Furthermore, in the absence of post-harvest management facilities, fruits and vegetables decompose into greenhouse gases. According to the National Centre for Cold Chain Development, every wasted ton of fruit and vegetables decomposes into approximately 1.5 tons of CO2 equivalent in greenhouse gasses (GHG)[7].

Adequate post-harvest infrastructure such as appropriate pre-cooling units, packhouses, cold storage facilities, refrigerated reefer vehicles, etc. can reduce produce loss and support post-harvest activities to enable easy access to markets for farmers while also reducing emissions from wasted produce.

The absence of suitable cooling and refrigeration technologies not only has adverse impacts on a country’s produce and farmer’s income but also limits access to proper healthcare facilities such as medicines and vaccines in public health centres. India faces up to 25% vaccine losses, even before vaccines reach doctors and patients, due to inadequate cold-chain infrastructure, as per the immunisation technical support unit, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

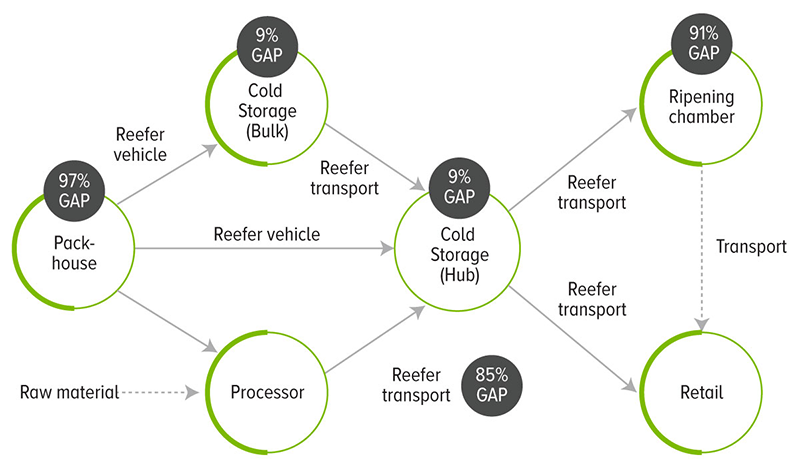

There is a huge gap in India’s cold chain infrastructure as per India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP) 2019 — pack-houses (97%), ripening chambers (91%), reefer transport (85%) and cold storages (9%), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Gaps in Overall Cold-Chain Sector in India (%)[8]

Figure 1: Gaps in Overall Cold-Chain Sector in India (%)[8]

However, these gaps at each link of the cold-chain present an opportunity to integrate climate-friendly, low cost and low energy cooling & refrigeration technologies in new and upcoming cold-chain infrastructure. As per ICAP 2019, energy-efficient cold-chain and refrigeration have an energy-saving potential of around 30% and would reduce refrigerant demand by 11% from business as usual.

Therefore, for the successful development of cold-chain infrastructure, the need of the hour is the implementation of robust policies and regulations to ensure that energy efficiency and clean energy are an integral part of the new and upcoming cold-chain infrastructure, along with easy access to finance for farmers, Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) and other users in the cold-chain sector. Increasing awareness and technical know-how about climate-friendly, sustainable and energy-efficient cold-chains is also an essential intervention required amongst the key actors responsible for planning, building, operating, maintaining and monitoring the cold-chain infrastructure in India.

AEEE’s Intervention for transitioning towards Sustainable and Accessible Cold-Chain Infrastructure in India

AEEE is working at the grassroots level to bring in the transition towards sustainable and accessible cold-chain infrastructure in rural India by i) deploying low cost and low energy cooling & refrigeration technologies, ii) understanding the grassroot level challenges, and iii) facilitating the development of sustainable and accessible cold-chain infrastructure in rural India under its flagship project: Improving Rural Livelihoods through Energy-Efficient Cooling & Refrigeration in India, with support from Good Energies Foundation. The key stakeholders under this project are FPOs, small and marginal farmers, rural healthcare centres and small retail shops, technology providers, resource institutions in the rural development sector, policymakers and sectoral experts.

The project is envisioned to act as a catalyst to support the Government of India’s goal of doubling farmers’ income and reducing food loss by advancing the development and implementation of efficient cold-chain infrastructure. It also fosters the implementation of ICAP 2019 recommendations associated with energy-efficient refrigeration technologies by promoting the adoption of low cost and low energy refrigeration technologies and conducting capacity building and training workshops for technicians, farmers and other stakeholders who would be the end-users or operators of the deployed technology.

Read more about the project here.

This blog is written by Srishti Sharma with inputs from Sangeeta Mathew and Tarun Garg